A version of this post originally appeared in the KLH Sustainability blog.

Last month, I presented at the International Water Association’s Efficient Water 2017 conference. The quality of the content and people at the conference was incredibly high, better than many other events I’ve attended recently. A large part of this is due to the fact that the water sector is finally moving beyond the engineering details of pipe, pumps and membranes and into the reality of the role of people in sustainable water management. There were conversations on policy and regulations, development, behaviour change, customer engagement, demographics, incentives and market mechanisms, retrofits, strategic planning, university collaboration, home visits, apps for data sharing, certification, taxes, real estate transactions—and that only covers the sessions I was able to attend!

The positive and dynamic energy of the conference is tainted in my memory, however, by a statement one presenter made. I won’t call him or his company out specifically (though, he was white, male and works for a water utility), but what he said was a jarring reminder of how many in the industry still act, even if thinking among industry leaders has matured. He said (and I paraphrase), “I hate the word engagement. I don’t care about engagement. I just care about education.”

That may sound innocuous enough on the surface—semantics, even. But it does illustrate a fundamental problem with the way professionals (and this isn’t specific to water) all too often show disdain, for customers, the public and people in general.

So, what’s the difference between education and engagement?

Education in this context flows in one direction. It’s the all-knowing utility/city/property owner teaching the customer/public/resident about facts. Often, the theory is that X (climate change, water scarcity, waste, etc.) would be better if only people were educated about it. That’s not entirely incorrect, but it ignores the fact that people aren’t stupid and there are many reasons for why people make the decisions they make, a lack of information is only one part of it.

Engagement, on the other hand, is two-way. It acknowledges that people aren’t passive, that they don’t necessarily respond to being told what to do, and they often offer lessons for professionals to learn, too.

Engagement, on the other hand, is two-way. It acknowledges that people aren’t passive, that they don’t necessarily respond to being told what to do as though they are children and they often offer lessons for professionals to learn, too.

The beauty of this conference was that it showed with many examples the multi-dimensional nature of, and multiple avenues for, engagement and why it matters.

Many of the sessions were about tools to help people make their own decisions, going beyond simply educating them about the problem or what to do. One panel brought together representatives from the US Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense, Australia’s Smart Approved Watermark, the EU’s Water Label and the UK’s Waterwise Checkmark to discuss water efficiency labelling programmes and how they can all do more to improve uptake and consumer choice. Northumbrian and Thames Water described their home visit programmes H2eco, Every Drop Counts and Smarter Home Visits, which involve in-person, in-home water use assessments and tailored solutions for water efficiency. While the programmes already provide good outcomes, most are continuing to do more to improve the way they engage. A few speakers presented on DAIAD, an open source technology system that measures your shower water use and provides real time information to your phone to help adjust your water use.

The DAIAD technology and the rise of smart meters has shown that data can be collected on more than just water quality or utility-scale water usage, it is also being collected at the micro-scale in ways that can teach the industry more about behaviours and demographics.

An example of this came from multiple speakers who talked about how improved meters and data collection have allowed utilities and researchers to analyse water use patterns and develop new ways of classifying users. These more detailed ways of segregating users reflect how people act and respond differently due to demographics, type of dwelling, location and even what time they get up in the morning. Having this information helps utilities and water advocates understand the different actions, attitudes and approach of different types of people and how that impacts on water use (and beyond). They can then better tailor engagement to help different water users.

Too often, professionals make assumptions about other people’s behaviours based on their own, which in industries that are not particularly diverse, mean the assumptions are often wrong. With better quality engagement, we can understand water users better for the benefit of the industry, the user and the environment. Success happens when we work with people to make changes, not when we summarily tell them to make a change.

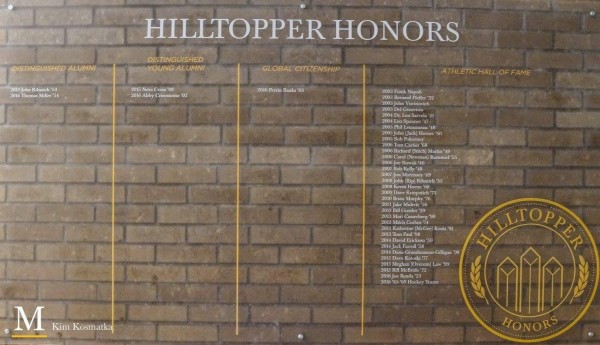

I was honored by my high school last month to receive the Marshall School Distinguished Young Alumni Award. Alas, I wasn’t able to make it to the ceremony, but my amazing filmmaker sister, Allison, was kind enough to create a thank you video for me to send to the ceremony instead!

I was honored by my high school last month to receive the Marshall School Distinguished Young Alumni Award. Alas, I wasn’t able to make it to the ceremony, but my amazing filmmaker sister, Allison, was kind enough to create a thank you video for me to send to the ceremony instead!